This post has been a long time in coming. And not just because it’s taken me a while to write it. But because it’s taken me a while to learn it. Like many home cooks, when it came to meat preparation, I was stumped. I didn’t understand the different cuts of meat or how to prepare them. After lots of reading, and a hands-on butchery class at The Center for Kosher Culinary Arts, I feel like I finally have a good grasp of kosher meat preparation and handling.

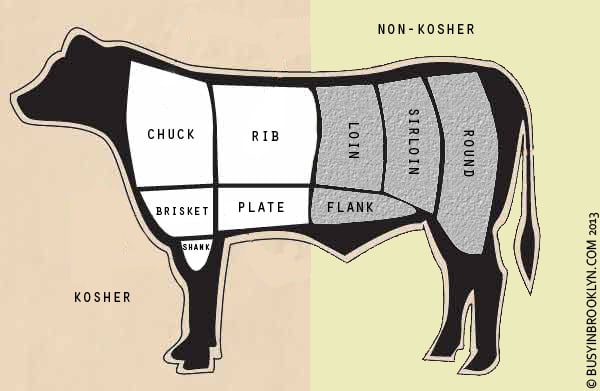

First things first: Where does the meat that we eat actually come from? The different cuts of meat that you buy at the butcher come from a steer. The steer is cut up into 9 sections, or PRIMAL CUTS, five of which are used for kosher consumption in the U.S. (the hindquarters require the removal of the sciatic nerve in a process called nikkur to render it kosher, which is only done in certain countries/communities by a specialty-trained menakker). The chuck, rib, brisket, shank and plate are cut into subprimals or fabricated cuts, which is what you see at the supermarket.

The most important thing to understand about the beef that we eat is where it comes from. Meat is made up of muscle and connective tissue. The more the muscle is used, the more connective tissue it will have causing the meat to be tough. For example, the chuck, which is the shoulder of the steer, is one of the most used parts of the animal resulting in a tough cut of meat.

Why does it matter where our meat comes from? Well once we understand the nature of the meat (if it’s tough or tender) we will know what type of cooking method it requires. Tough cuts of meat needs moist cooking to break down the muscle fibers and connective tissues. Tender cuts require dry heat cooking methods to firm up the meat without drying it out.

Now, let’s get into fabricated cuts and how they are broken down.

Unfortunately, for the kosher consumer, it’s hard to know what you’re really getting in the butcher shop. Kosher butchers (and butchers in general) tend to name their cuts however they like. That being said, these are the most general fabricated cuts that you’ll find:

CHUCK:

Chuck roast is often sold tied in a net and includes the Square Roast (top portion) and the French (or Brick) Roast (bottom portion). Since the chuck portion is very tough, it is often cubed and sold as stew meat as well. Kolichol is another tough cut from the shoulder section, and is great to use in the cholent or wherever a recipe calls for pot roast. Unlike chuck roasts that require moist heat cooking to tenderize the meat, Shoulder London Broil & Silver Tip Roasts (used to make Roast Beef) that are also cut from the shoulder, can be roasted using a dry heat cooking method until medium-rare.

One of the most popular and tender cuts from the shoulder is the minute steak roast. You would probably recognize it from the thick piece of gristle that runs down the center. When the roast is sliced horizontally above and below the gristle, the resulting cuts are often called filet split and are perfect for quick cooking in stir fry’s or wherever recipes call for quick grilling (such as london broil or flat iron steak).

A note about London Broil: London Broil is not actually a cut of meat, but rather a method of preparing the meat by broiling or grilling marinated steak and then cutting it across the grain into thin strips. Butchers use different cuts of meat for this, some more and some less tender. If you are curious as to where the London Broil is cut from, simply ask your butcher.

RIB:

Ribs are the most tender cut of kosher meat because the muscles in this area are not worked as much. Ribs should always be cooked using a dry heat cooking method. The rib section includes, rib steaks, ribeye steaks, club steaks, delmonico or mock filet mignon (which uses the center EYE of the rib). There is also a great cut known as the Surprise steak – a flap that covers the prime rib and is tender and delicious. Above the surprise steak is the “Top of the Rib” which some butchers call the “Deckle”. This is the one exception to the rule of the rib section. Top of the Rib is a tougher cuts and benefits from moist heat cooking.

Besides the rib primal, ribs can also be found in the chuck primal, which includes the first five ribs of the ribcage. That is where flanken and short ribs comes from. Short ribs are strips of meat & fat that are cut from between the ribs, while flanken is a cross-section cut, including pieces of the rib in between the meat & fat. Spare ribs are short ribs that have been cut in half lengthwise. Both short ribs and flanken benefit from moist heat cooking.

PLATE:

The plate sits below the rib primal and includes the flavorful skirt and hanger steaks. Both have a high salt content and benefit from quick grilling.

BRISKET:

Brisket is the breast of the steer and is an extremely tough cut. A whole brisket can weigh as much as 15 lbs. Brisket is often sold as 1st and 2nd cut. First cut brisket is flat and lean. It is much less flavorful than the second cut, which is smaller but fattier. In general, fattier meat will always yield a tastier product. Fat is flavor, so when possible, always opt for a well-marbled cut over a leaner one. You can always refrigerate the meat and remove the congealed fat later on.

First cut of brisket tends to cut nicely, while second cut tends to shred, making it perfect for pulled beef. Corned beef & pastrami are popularly made from brisket. Corned beef is pickled while pastrami is smoked.

FORESHANK

The foreshank is very flavorful and high in collagen. It includes the shin and marrow bones. Because collagen converts to gelatin when cooked using moist heat, foreshanks are excellent for making stocks.

ADDITIONAL PARTS

In addition to the primal cuts of the animal – there are other edible parts of the steer including the neck (mostly used ground up due to it’s connective tissues), cheek (great for braising), sweetbreads (thymus gland), liver, tongue and oxtails (hard to find kosher due to the complications involved in removing the sciatic nerve).

GROUND BEEF

Ground beef can come from any part of the animal, but it is usually made from lean cuts and trimmings. Grinding the meat helps to tenderize it, so the toughest cuts are often used. When purchasing ground beef, keep in mind that the leaner the meat, the drier your end product will be. 80% lean to 20% fat is a good ratio.

OTHER CUTS NOT MENTIONED

There are lots of different cuts available that are not mentioned here, and the reason for that is because every butcher has different scraps and pieces of leftover meat that they choose to label at their own convenience. Pepper steak at one butcher might come from the chuck and at another butcher, from the deckle. If you want to use your meat for a specific purpose, and you don’t want to have to braise it for a long time in order to tenderize it, order a specific cut from your butcher, or ask where the prepackaged meat comes from.

GRADING

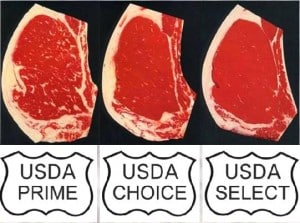

All meat is graded by the USDA to ensure that it is fit for human consumption. Grading provides a system by which distributor (and consumers) can measure differences in quality of meats. Grades determine the tenderness and flavor of the meat base on its age, color, texture and degree of marbling. USDA Grades include: Prime, Choice, Select and Standard. You’ve probably heard of USDA Prime Grade meats. They are often used in fine restaurants. USDA Choice is the most commonly used grade in food service operations.

COOKING METHODS:

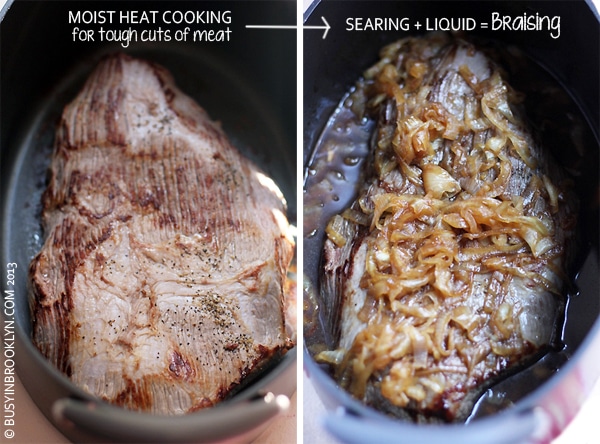

As I mentioned above, once you know whether your meat is tough or tender (due to muscle movement & connective tissue) you will understand how to cook it. Tough meat requires slow, moist heat cooking to help break down the connective tissue and tenderize the meat. Tender meat requires dry heat cooking to firm up the proteins without breaking down connective tissue.

DRY HEAT COOKING

Dry heat cooking can include broiling, grilling, roasted or sauteing/pan-frying. Meat should be cooked at high temperatures to caramelize their surface. To determine doneness, check the temperature with a meat thermometer. Over time, you will learn to “feel” for doneness based on the meats resistance when poked with a finger.

Thermometer readings:

very rare (sometimes referred to as “blue” meat) 120-125

rare (deep red center) 125-130

medium rare (bright red center) 130-140

medium (pink center) 140-150

medium well (very little pink) 155-165

well done (all brown) 160+

MOIST HEAT COOKING

Moist heat cooking includes simmering (used for corned beef and tongue) and combination cooking methods: braising and stewing.

Combination cooking methods use both dry and moist heat to achieve a tender result. Meats are first browned and then cooked in a small amount of liquid. Wine and/or tomatoes are oftened used as the acid helps to break down and tenderize the meat. The meat and liquid are brought to a boil over direct heat, the temperature is reduced and the pot is covered. Cooking can be finished in the oven or on the stove top. The oven provides gentle, even heat without the risk of scorching. To determine doneness when braising or stewing, the meat should be fork tender but not falling apart.

The main differences between braising and stewing are that stewing uses small pieces of meat, while braising uses a single, large portion. In addition, braising requires liquid to cover only 1/3-1/2 of the meat while stewing requires that the meat be completely submerged in the liquid.

RESTING & CUTTING MEAT

When meat has finished cooking, it’s always important to let it rest (10-20 minutes) before slicing. Resting allows the juices to redistribute themselves, and cutting into the meat too early will cause all the juices to run out of the meat.

Another thing to keep in mind when cooking meat is CARRYOVER COOKING. When meat is finished cooking and removed from the heat, the internal temperature still continues to rise while the meat continues cooking. Therefore, keep in mind carryover cooking when using dry heat cooking methods. If you are looking for a medium doneness, and you pull your meat off at 150 degrees, the meat will continue to cook until it’s temperature reaches about 155, resulting in medium well doneness.

As mentioned, meat is a group of muscle fibers that band together to form muscles. When cutting meat, it’s important to cut against the grain (perpendicular to the muscle fibers) in order to shorten the muscle fibers so that they are more tender. Cutting parallel to the muscle fibers results in chewy, stringy cuts of meat.

MEAT RECIPES

beer braised brisket with onion gravy

pulled BBQ brisket

pepper steak with plum sauce

spaghetti squash bolognese

Rosh Hashanah roast

london broil with red wine reduction

Really nice job

I am speechless

You did avery thorough job

I am proud of you

You are ready to replace me (if you could only filet)lol

This is soooo informative!

Great job Chanie, I think so many of us are constantly confused and this clears up so many things. Now I know why every cut of London Broil I buy is so different.

This is a great guide! I will definitely pass this on.

Interesting article, although the idea that the entire back half of a cow is not kosher is a well perpetrated myth. There is a small sinew in the hindquarter that needs to be separated from the rest of the meat. There are even a few well-trained shochets in Israel who are qualified to remove the sciatic nerve. I had the pleasure of watching famed Italian butcher Dario Cecchini take apart a hindquarter of a cow, and saw the nerve myself. It is hard to remove from a small portion of the leg, but otherwise, all other cuts from the cow are fine.

Someone told me that in America, it is too time consuming to remove the veins from the back half of the cow. It is sold off for non-kosher. In Isreal, there is no one to purchase it. No goyim or dog food manufactures. Meat is a lot more expensive there, so they don’t want it to go to waste. Also some of it comes from South America.

That is absolutely correct! As a semica student I’ve seen several demonstrations of nikkur (deveining the gid hanashe which runs through the back of the cow) and the only reason the back is not sold is due to economics. It is a shame that the back is not sold, because there are many fine cuts of meat which are contained in the back of the cow.

I agree!

Fantastic article, thank you so much!

Yocheved

Unfortunately this is almost as ignorant as calling the back half not kosher… The main reason most of the Ashkenazi world doesn’t use the back half is in fact because of the chelev (which is biblically prohibited). The gid hanashe (sciatic) is only a small part of it and may be not at all.

In Israel there are sefardi hashgachois that do nikkur on the back half and it is widely available.

In some Ashkenazi communities in Europe it was done, and in some not. Over time, fewer and fewer communities had the highly skilled menakrim to od the job.

The question became, if “your minhag” is not to treiber the rear, can you eat meat treibered by a menaker in a different community where it was still done? There were some rabbonim who were strict about this, but I believe the common psak was to allow it.

Rabbi Kaganoff has an excellent article on this.

https://rabbikaganoff.com/may-an-ashkenazi-eat-sirloin/

A really amazing guide! Great Job!

this is seriously awesome! i’m sure i will refer back to it again and again!

Great guide! Shared this with everyone!

Required reading!

As usual, I am doing last minute Chag cooking. I bought a grass fed 7 1/2 pounds rib roast (no more details) from Uruguay. Oy, so is it tender or tough? Thanks so much Chanie. Chag Sukkot Sameach.

Pam :)

Rib roast is tender. Make sure to cook using dry heat and don’t overcook (you want it pink in the center). Sear in the pan, put in oven at 400 until internal temp reaches 140.

Rib roast is a very tender cut, and normally should be cooked with dry heat. However, grass fed beef does not follow the rule. It requires moist heat to be tender. Another possibility is to use a commercial meat tenderizer such as Adolph’s, but I don’t know if Kosher versions are available. Meat tenderizers work wonders.

I could never bring anything into my home – much less my kitchen and then table – with a name of such a rasha.

Get roast to room temp, preheat oven to 500, bake for 15 minutes then drop to 350 and bake 20 minutes per pound, let’s sit covered for 30 minutes before slicing, time backwards to serve on time for Shabbat or Chag. Grass fed is great.

thank you for all of your hard work! this was a great guide – approachable and easily understood.

thanks Stephanie!

I’m trying to recall the roast beef my mother made in 1940s and 50s with a circlular bone size of silver dollar, hole in middle and square inch approx of gristle. I know a cheap cut, stringy meat. Loved that gristle. Anyone know?

Sorry Lee, maybe try your local butcher?

That was round, a hindquarter cut. According to this article, not Kosher, but a really good cut of meat. The gristle suggests it was not Kosher, also.

i’ve been dry-roasting french/square/beaver roasts for many years, despite the conventional wisdom. i do like beef rare, so maybe that’s why. paula wolfert has a recipe in her book on slow mediterranean cooking that calls for searing a roast in a dutch oven on the stove top, turning off the fire, then n leaving it, with the lid on, for 45 minutes. the “carry-over” from the searing heat yields a roast that’s evenly rare throughout.

re cuts from the hindquarters: my daughter has some russian friends, among whom there’s a kosher butcher in brooklyn who is trained in removal of the sciatic nerve, and the hind parts are kosher. i’ve been waiting for a kosher leg of lamb and maybe some fillets for beef stroganoff, so i’ve yet to believe it’s true.

Interesting technique, thank you for sharing!

Where is the kosher butcher who removes the bad stuff from the rear of cow

Hi Zesa, sorry but I’m not familiar with anyone in particular.

This article has been so informative !!! Thanks for the guide!

Thanks Chanie!

Thanks for this great post! I did a google search to try to understand different cuts of meat and this post came up. Easy to read and just what I was looking for!

Thanks Rendy, I’m so glad this was helpful for you!

Where does the “deckle” roast cut come from? Do you have any recommendations on how best to prepare one?

Deckle is from the top of the rib, it’s a tough cut and therefore it benefits from braising. You can use any braised roast recipe, just cook low and slow for 3 hours or so.

Great article! So how would I cook a whole delmonico club roast? Thanks

Hi Mindy! The delmonico is what it’s used to make club steaks. It’s the last part of the chuck, right before the ribs, and is a tender cut which would benefit from dry roasting. Of course it can be braised as well, but it does not need to be.

Very helpful, you’ve worked hard. Now i know why some meat is called top rib and needs different cooking from rib

Anita

Thanks Anita, I’m glad you found my meat guide helpful!

Thank you thank you–most thorough and helpful guide to kosher meat cuts I’ve found to date!

That is quite the compliment Ruth, I’m so glad you found it helpful!

Hi! thanks for all the info, great reading!

can you please tell me whats the best cuts as alternative for:

Sirloin?

fillet?

and what is prime bola? (what part and tender or tough meat?)

and top rib joint (tender or tough?)

Thanks again and have a good shabbat!

Hi, I would guess that ribeye would be the best kosher replacement for sirloin. I’m not sure what cut you are referring to as fillet. Do you know where it’s cut from? …There are no cuts called prime bola here in America. As for top rib joint, we have something called “top of the rib” which is not tender and would require braising.

Filet (filet mignon) usually refers to the tenderloin, sliced as steak. It is included in the T-bone and Porterhouse steaks, also. These are all from the loin, and therefore according to this article not Kosher, though evidently some posters are aware of Kosher butchering techniques that remove the offending parts.

Prime bola is one of the parts of the shoulder its the bigger part the other 2 parts are the smaller one which are called round bola and the other one is called side bola

How do you know which way the grain goes?

You can actually see it – the grain looks like lines of muscle fibers. Go in the opposite direction.

What’s better, chuck eye in a net or French roast?

Thank you!

They’re both flavorful roasts that are cut from the chuck. I would probably go with the french roast because it’s not in a net and will slice up nicer than the chuck eye.

Great web page. I am a Goyim that tries to live by HaShem’s ways. I live in Texas and do some deer hunting. I know that it is not Kosher to hunt but I make sure the kill is very clean and painless and also pour all blood into the ground and cover with dirt, per Leviticus 17:13 (regarding hunting) and remove the blood with kosher salt. Do you know any resource on how to removing the sciatic nerve.

I also believe the day is coming when ever Goyim will call the Jewish people and Israel blessed and grieve for how we have treated HaShem’s chosen people.

Hi Rick and thank you for commenting! Unfortunately, I do not know anything about the slaughtering process, just the butchery and cookery of meat. Best of luck to you!

“Besides the rib primal, ribs can also be found in the chuck primal, which includes the first five ribs of the ribcage. That is where flanken and short ribs comes from. ”

This is completely wrong. Flanken/Short Ribs is the ends of the plate (which you only attribute the hanger and skirt steaks to). The ribs, i.e. “Baby back” that come from the chuck or rib portion are the backs of the rib steaks and rarely have much meat due to the high demand for the steaks

finally a person that knows how to write.

Excellent!

Thank you so much your article was extremely helpful.

I have a bbq seasoned club steak and bbq ribs from the butcher, which is better for shabbat meal, and which is the bet way to make them tender?

The ribs are probably nicer to serve. To tenderize them, I would add some liquid (beer, wine, or stock) and braise them low and slow at 325 for 3 hours or so.

Thank you so much for this article. How would you cook a medallion steak?

What is best for me to use in a cholent: brisket or mock shoulder roast?

Why is the rear portion marked not kosher? where is it coming from? In Israel there is no problem getting these rear portions kosher.

Please explain why you say they are not kosher.

In America, we don’t use the rear portion due to complications involved in removing the sciatic nerve.

Using a kosher corned beef and cooked on top of stove, does the water need to be changed, any suggestions

I simmer it until tender, you don’t need to change the water.

What is the dry heat cooking for silver tip roast. Please please. I want to cook it for yontif.

You rub with oil, salt, pepper and herbs and bring to room temperature. Roast, uncovered, at 400 for 25 minutes, lower the heat to 350 and continue roasting until medium rare (140 degrees), you will need a meat thermometer to check it.

My mother would always attempt to serve us flanken. I hated it, because I’ve always been grossed out by any fat on meat or chicken, and couldn’t stand the stringy texture. But once in a while she’d make kalchel, which I loved. I guess it cost more, so it was a rare treat. I’ve spent my adult life trying to figure out what cut of beef it is and, despite my computer search prowess, I still can’t find any information about it. Can anyone enlighten me? Thanks.

Hi! Kolichol is meat cut from the shin. It makes a great pot roast! We often use it in our cholent on Shabbat.

Thank you, Chanie. If I wanted to buy it, what could I ask for besides “meat cut from the shin?”

Kolichol!

I’m aiming at preparing steak tartar. My thoughts are using a prime grade delmonico or a surprise steak. Any thoughts, including suggestions based on experience, if any?

I’ve never made steak tartare before but I would suggest prime grade ribeye. Delmonico can work depending on where the butcher cuts it from. Unfortunately it’s a bit confusing since butchers tend to label different cuts as Delmonico. If it’s the ribeye of the chuck then you can use that.

hi

im trying to make recipe which calls for rack of ribs. is that the same as back of ribs?

Not necessarily, but you can substitute either one in your recipe.

This article was fantastic! You demystified the world of kosher meat cuts. It is so wonderful that you not only gave the various names the cuts could have and indicated where they are located on the cow but you gave us cooking methods.

Thank you so much!

I’m so glad you found it useful!

Amazing article! Super helpful and demystifying! I bought meat labeled as “Boneless BBQ Ribs-Finger Meat” and not having any luck figuring out if its tender or tough. Any tips?

Finger meat is the meat between the ribs. You can grill it or braise it.

Thank you for this post. I have a question: what part of Kosher meat would you use to substitute the sirloin steak?

Thank you.

ribeye or New York strip steak.

Just ordered from a new butcher and came across your article. Sooo helpful. Love all the comments, hints and recipes too!!